Cochrane review on industry sponsorship

Many papers have been published that compare clinical trial publications sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry with those not sponsored by industry. Last week, the Cochrane Collaboration published a systematic review by Lundh et al of those papers. The stated objectives of the review were to investigate whether industry sponsored studies have more favourable outcomes and differ in risk of bias, compared with studies having other sources of sponsorship.

There are some rather extraordinary things about this review.

The most extraordinary thing is a high level of discordance between the results and the conclusions. This is a little odd, since one of the outcomes they investigated was whether industry studies were more prone to discordance between results and conclusions, so you’d have thought Lundh et al would understand the importance of making them match.

But nonetheless, they don’t seem to. The conclusions of the review state “our analyses suggest the existence of an industry bias”. In their results section, however, they investigated various items known to be associated with bias, such as randomisation and blinding. They found that industry studies had a lower risk of bias than non-industry studies. I’ve written before about bias in papers about bias, and this seems to be another classic example of the genre. This is disappointing in a Cochrane review. Cochrane reviews are supposed to be among the highest quality sources of evidence that there are, but this one falls a long way short.

It appears that they drew this conclusion because they found that industry sponsored trials were more likely to produce results or conclusions favourable to the sponsor’s product than independent trials (although that finding may not be as sound as they think it is, for reasons I’ll explain below). They therefore concluded that industry-sponsored trials must be biased, because they’re systematically different from independent trials. That does not make logical sense. Three explanations are possible: either industry trials are biased in favour of favourable results, independent trials are biased towards the null, or the two types of trial investigate systematically different questions. Any of those is possible, and they have not presented any evidence that allows us to distinguish between the possibilities. However, given that where they did measure bias, they found less bias in industry studies, the conclusion that the bias must be a result of industry sponsorship seems hard to support.

Another of Lundh et al’s conclusions was that industry-sponsored trials are more likely to have discordant results and conclusions, for example claiming that a result was favourable in the conclusions when the results don’t support that conclusion (I know, it’s hard to imagine anyone could do that, isn’t it?) This is stated as fact, despite the little drawback that their meta-analysis estimate of the difference between industry and non-industry studies did not reach statistical significance. Also, there is one study I happen to be aware of which would seem to be relevant to this analysis (Boutron et al 2010) as it investigated “spin” in conclusions, which seems to me to be exactly the same concept as discordance between results and conclusions. That study, for reasons not explained in the paper, was not included in their analysis. It can’t be because they didn’t know about it, as they cited it in their discussion (and, incidentally, misrepresented its results when they did so). Boutron et al found no significant difference between industry and non-industry studies in the prevalence of spin in conclusions, so if it had been included it could have weakened their results further.

I mentioned above that I was not totally convinced by their conclusion that industry-sponsored studies are more likely to have results favourable to the sponsor's products than independent studies. Oddly enough, until I read this systematic review, I had taken that assertion as established fact. I have seen various papers that found that result, and had felt that the finding was robust. However, I now have my doubts.

Here’s why.

One of the big challenges for any systematic review is the problem of publication bias. This is the tendency of positive studies to be published and negative studies to be quietly forgotten. This is a big problem, because if you look at all published studies in a systematic review, you are actually looking at a biased subset of studies, usually those with positive results.

A good systematic reviewer will investigate the extent to which this is a problem. The Cochrane handbook, the instruction manual for Cochrane systematic reviews, recommends that reviewers investigate publication bias by means of funnel plots or statistical tests. The idea behind such methods is that large studies are likely to be published whatever the results, as so much has been invested in them that the final stage of publication is unlikely to be overlooked, whereas small studies may well be unpublished if they are negative, but are more likely to be published if they are positive. If you see a correlation between study size and effect size, with smaller studies showing larger effects than larger studies, that is strongly suggestive of publication bias. For those who are not familiar with these concepts, Wikipedia has a good explanation.

However, despite the recommendation in the Cochrane handbook that reviewers should investigate publication bias, Lundh et al seem to have largely overlooked it. They mention a small number of studies published only as conference abstracts or letters, and found they provided similar results to the main analysis, and concluded that publication bias was therefore unlikely. This is a very superficial examination of publication bias that falls well short of what should happen in a Cochrane review.

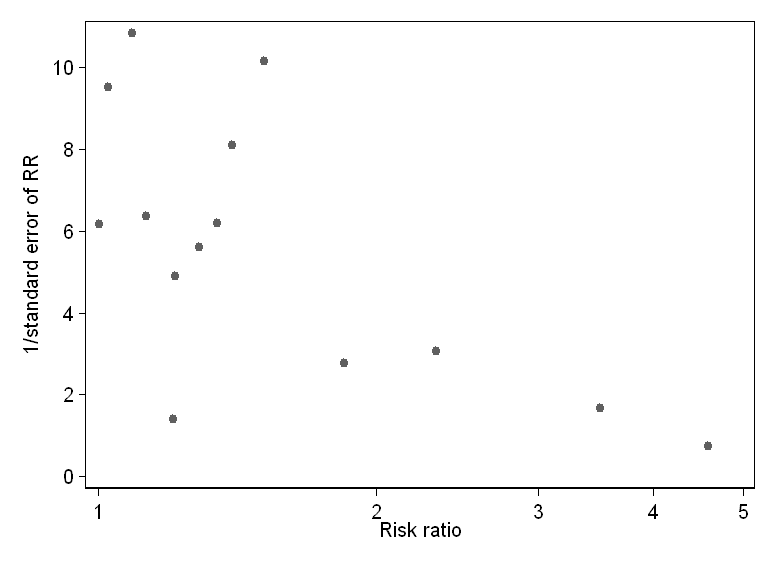

Fortunately, they present their data in full, so it is easy enough for anyone reading the review to do their own test for publication bias. So I did this for their primary analysis: comparing industry and non-industry studies for their probability of producing favourable results. The results are strongly indicative of publication bias. This is what the funnel plot looks like:

As you can see, there is striking asymmetry here, with most small studies (those towards the bottom: the y scale is actually the reciprocal of the standard error of the relative risk, but this is strongly related to study size) having much larger effects than larger studies, and no small studies showing smaller effects. This is very strongly suggestive of publication bias. I also did a statistical test for publication bias (the Egger test, one of those recommended in the Cochrane handbook), with a regression coefficient for effect size on standard error of 2.3, which was statistically significant at P = 0.026.

So there is clear evidence that these results were subject to publication bias. It is therefore highly likely that their estimate of the difference between industry and non-industry studies was overstated. Maybe there isn’t really a difference at all. It’s very hard to tell, when the literature is not complete.

I could go on, as there are other flaws in the paper, but I think that’s long enough for one blog post. So to sum up, this Cochrane review had methods that fell short of what is expected for Cochrane reviews. Lundh et al found that industry sponsored studies, when assessed using well established measures of bias, were less likely to be biased than independent studies, and yet drew the opposite conclusion, based on nothing but speculation. This, in a study which investigated discordance between results and conclusions, is bizarre. Their main finding, that industry sponsored studies were more likely to generate favourable results than independent studies, appears to have been affected by publication bias, which makes it considerably less reliable than Lundh et al claim.

I am normally a great fan of the Cochrane Collaboration, which usually produces some of the best quality syntheses of clinical evidence that you will ever find. To see such a biased review from them is deeply disappointing.

[...] of bias in industry and non-industry sponsored studies as Adam Jacobs indicated in his recent blog. Also worth noticing in this respect is that unpublished data does not seem to be about negative [...]

[...] his book, and it seems that the answer to this question may have been affected by publication bias, as I blogged about recently. So while it may be true that industry sponsored studies are more likely to find favourable [...]

Response to comment by Adam Jacobs

We thank Adam Jacobs for the interest in our paper and would like to respond. The comment deals with three issues: the exclusion of the Boutron paper, the use of the term industry bias and possible publication bias.

First, Jacobs believes we should have included the Boutron paper (1). This paper was identified in our search, but excluded from our review because it did not meet the inclusion criteria pre-specified in our protocol. The Boutron paper deals with spin in conclusion of trials with statistically nonsignificant results. Spin can be focusing on results of subgroups or focusing on secondary outcomes in the discussion. This is something very different from concordance between results and conclusions investigated in our review (i.e. whether the conclusions agreed with the study results). Also, we did not misrepresent the Boutron paper as Jacobs suggests. Jacobs states that, “Boutron et al found no significant difference between industry and non-industry studies in the prevalence of spin in conclusions.” Boutron does not make this claim. In fact Boutron et al. writes “Our results are consistent with those of other related studies showing a positive relation between financial ties and favourable conclusions stated in trial reports.”

Second, Jacobs misstates our results by suggesting that we found that industry studies had a lower risk of bias than non-industry studies. We did not find a difference, except in relation to blinding, which we discuss further in our review. Furthermore, Jacobs actually seems to agree with our conclusion that the industry bias may be due to factors other than the traditional risks of bias that are usually assessed, e.g., randomization and blinding. That is just our point. For example, he states that the industry studies may “investigate systemically different questions”. We mention this possibility in our Discussion section. Based on the available external evidence (2,3), we believe that a plausible explanation for the more favorable results and conclusions in industry studies is that industry studies may be biased in design, conduct, analysis and reporting.

Third, Jacobs suggests that our results may be due to publication bias (i.e. that papers finding no difference in favorable outcomes between industry sponsored versus non-industry sponsored studies are not published) and criticizes us for not assessing publication bias using a funnel plot. However, as the Cochrane Handbook states (4) (section 10.4), there may be various reasons for funnel plot asymmetry, publication bias being one of them. Other reasons are true heterogeneity and risk of bias in the primary material being used in the meta-analysis. The included papers investigated many different drugs and devices and it is likely that any ‘industry bias’ may be different between the various types of treatments. Due to the anticipated heterogeneity of these papers, we did not assess publication bias using a funnel plot, as such a plot would be difficult to interpret as noted in the Cochrane Handbook. Instead, we included conference abstracts and letters in an additional analysis and found it had no impact.

To argue for his case about publication bias Jacobs presents a funnel plot of analysis 1.1 on the association between sponsorship and favorable results. Based on this funnel plot four small studies are outliers to the right and should provide evidence of bias. However, three of these studies were related to specific drugs (glucosamine, nicotine replacement therapy and antipsychotics) and the fourth study dealt with psychiatric research, a field where biased industry research has been well documented (5,6). So the study domain may explain the difference. Also three of the four studies had high risk of bias, which could also explain the findings and if we restrict the analysis to studies of low risk of bias (analysis 7.1) the results are less heterogeneous. Last, even if we assume publication bias to be present, to exclude the four papers from our analysis (the ones that should provide evidence for publication bias) has no impact on our analysis (RR 1.21 (95% CI: 1.12 to 1.32) instead of 1.24 (95% CI: 1.14 to 1.35)). A similar plot for conclusions (analysis 3.1) has two studies as outliers and excluding these studies from the analysis has no impact (RR 1.27 (95% CI: 1.16 to 1.38) instead of RR 1.31 (95% CI: 1.20 to 1.44)). We therefore completely disagree with Jacob’s statement that “there is clear evidence that these results were subject to publication bias. It is therefore highly likely that their estimate of the difference between industry and non-industry studies was overstated. Maybe there isn’t really a difference at all”. On the contrary, our findings that industry sponsorship leads to more favorable results and conclusions, are very robust.

In sum, none of the comments provided by Jacobs have any impact on our results.

Andreas Lundh, Sergio Sismondo, Joel Lexchin and Lisa Bero

References

1. Boutron I, Dutton S, Ravaud P, Altman DG. Reporting and interpretation of randomized controlled trials with statistically nonsignificant results for primary outcomes. JAMA 2010;303(20):2058–64.

2. Bero LA, Rennie D. Influences on the quality of published drug studies. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 1996;12(2):209–37.

3. McGauran N, Wieseler B, Kreis J, Schuler YB, Kolsch H, Kaiser T. Reporting bias in medical research - a narrative review. Trials 2010;11:37.

4. Sterne JAC, Egger M, Moher D (editors). Chapter 10: Addressing reporting biases. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention. Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org.

5. Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R. Selective

publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. New

England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(3):252-60.

6. Healy D. Pharmageddon. 1st edition. University of California Press; 2012.

Dear Andreas and colleagues

Many thanks for taking the trouble to write such a detailed reply to my post. Your comment deserves an equally detailed reply. I'll take your points one at a time.

"The comment deals with three issues: the exclusion of the Boutron paper, the use of the term industry bias and possible publication bias."

Actually, it was 4. I also mentioned the statement in your conclusions (specifically, in the plain language summary, although similar statements are made elsewhere) that industry sponsored studies had less agreement between results and conclusions than non-industry sponsored studies, despite the fact the you did not find a statistically significant difference between the two groups. I think to draw that kind of conclusion based on a non statistically significant result is misleading (particularly in a plain language summary, where your intended readers are less likely to be able to interpret the confidence interval for the RR correctly). Would you like to comment on why you think it's OK to draw conclusions based on a non statistically significant result?

As for the exclusion of the Boutron paper from your analysis, you write:

"The Boutron paper deals with spin in conclusion of trials with statistically nonsignificant results. Spin can be focusing on results of subgroups or focusing on secondary outcomes in the discussion. This is something very different from concordance between results and conclusions"

I must say that it seems like a rather fine distinction to me, especially given that one of the definitions of spin that Boutron et al used was "claiming or emphasizing the beneficial effect of the treatment despite statistically nonsignificant results". Nonetheless, I do appreciate the importance of prespecifying your inclusion criteria and then sticking to them, and that there will always be borderline cases, so thank you for your explanation.

"Also, we did not misrepresent the Boutron paper as Jacobs suggests. Jacobs states that, “Boutron et al found no significant difference between industry and non-industry studies in the prevalence of spin in conclusions.” Boutron does not make this claim."

Perhaps you didn't read the correspondence following the paper? It's true that Boutron et al did not report results on the difference between industry and non-industry studies in their main paper, but they did so in subsequent correspondence, and reported that there was no statistically significant difference between the groups (P = 0.6).

"In fact Boutron et al. writes “Our results are consistent with those of other related studies showing a positive relation between financial ties and favourable conclusions stated in trial reports.”"

Yes, they did indeed write that, but it simply wasn't supported by their data. In the correspondence, they acknowledged that they were not in fact justified in making that conclusion. I can't resist pointing out the irony of that happening in a paper about discordance between results and conclusions.

"Second, Jacobs misstates our results by suggesting that we found that industry studies had a lower risk of bias than non-industry studies. We did not find a difference, except in relation to blinding"

So in other words, you did find a difference.

Also, you report that 9 papers looked at composite measures of quality, and that 5 of them found industry studies were of better quality while 4 found no difference. It's not entirely clear to me why you didn't combine those results in a meta-analysis, but nonetheless, I would have thought it is reasonable to conclude based on those results that industry studies were probably of better quality.

"Furthermore, Jacobs actually seems to agree with our conclusion that the industry bias may be due to factors other than the traditional risks of bias"

I'm not sure why you would think that. There is a premise behind that statement that there is such a thing as "industry bias". As I thought I had made clear (though perhaps I didn't make it clear enough), I really don't agree that you have shown any evidence that such a thing exists.

"Based on the available external evidence (2,3), we believe that a plausible explanation for the more favorable results and conclusions in industry studies is that industry studies may be biased in design, conduct, analysis and reporting."

The available external evidence is considerably wider than those two papers you cite. I haven't read your reference No 2 (Bero et al 1996) and sadly it's behind a paywall (though I'd be fascinated to read it if you'd be kind enough to email me a copy), but I would question the relevance of a single paper from so long ago. It might be better to look at a more recent systematic review, such as Schott et al 2010. The results they found were not totally consistent, but nonetheless pointed towards better quality methods in industry sponsored studies.

Your reference No 3 (McGauran et al 2010) does not seem to provide any useful information on whether the methods of industry sponsored studies are better or worse than independent studies.

Finally, turning to the question of publication bias and my funnel plot, you are of course quite correct to state that funnel plots are hard to interpret, and that the asymmetry of the funnel plot does not prove the existence of publication bias. You are also correct that it is entirely reasonable to expect heterogeneity among the different studies. However, it does seem rather a coincidence that the studies with the largest effect sizes were also the smallest. If the heterogeneity were not a result of publication bias, there would be no particular reason why that should be true.

Ultimately, any questions about publication bias are, by their very nature, almost impossible to answer. I certainly cannot prove that your results were affected by publication bias. However, you equally cannot prove that they were not. I think the correct interpretation is that the asymmetry in the funnel plot should alert us to the possibility that publication bias could be present, and that the results should therefore be interpreted cautiously.

[...] published in 2012 looked at the effect of industry sponsorship on clinical trial publications. It found that bias was less likely in industry sponsored research, but concluded that it was more li... Granted, that review was by different authors to the Tamiflu review, but it does suggest that there [...]