Minimum alcohol pricing

A lengthy article was published in the BMJ today about the decision the government made last year to abandon their previously-stated plans on minimum alcohol pricing. As you might expect from the BMJ, with their strident anti-industry agenda, the article claims this is all about a terrible conspiracy in which the evil drinks industry and the government collude together to put the interests of the evil drinks industry ahead of public health.

The reality, I believe, is a little more complicated than that.

I should state straight away that I do not doubt that minimum alcohol pricing would have beneficial effects on public health. Alcohol causes a lot of harm. When people get drunk, they get into fights and have accidents. The long term consequences of over-use of alcohol include many diseases, most notably liver disease, but also many cancers.

It is an almost universal law in economics that if you put the price of something up, consumption goes down. How much it goes down may be open to debate, but it is inconceivable that putting the price of alcohol up wouldn't reduce consumption. So a minimum price for alcohol, if set above the market rate for the cheapest forms of alcohol, would undoubtedly reduce alcohol consumption, and it is likely that that would have beneficial effects on public health.

So, case closed then? Minimum alcohol pricing is a thoroughly good thing, and if the policy has been dropped, then that must be evidence of an evil conspiracy, right?

Well, no. A policy such as minimum alcohol pricing does not magically affect public health in isolation without having wider consequences. It also has economic consequences, and the economic consequences of minimum alcohol pricing would be considerably less welcome than the public health consequences.

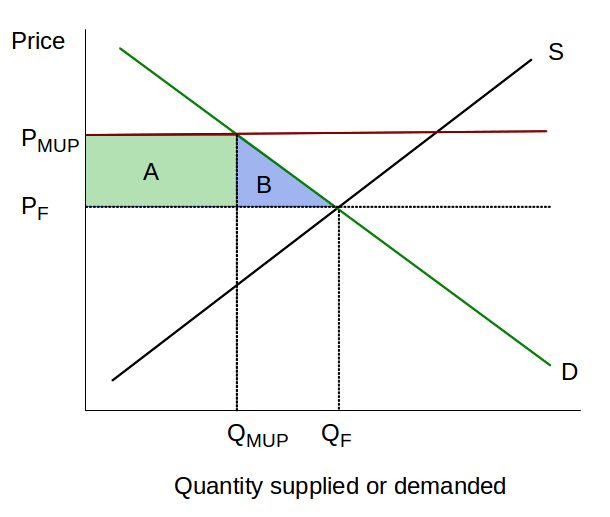

To explain the economic consequences of minimum alcohol pricing, it's time for some economics geekery. Here's a little graph.

This graph shows how minimum alcohol pricing, if set above the free market price, would affect consumption. (If you're not familiar with this kind of supply-and-demand graph, here's an excellent explanation on YouTube from economics lecturer Jodi Beggs.) The upward-sloping black line S represents the amount of alcohol that the drinks industry is willing to supply at different prices: the higher the price, the more it is worth their while to supply. The downward sloping green line D represents the consumer demand curve. The higher the price, the less alcohol consumers will want to buy. In a free market, supply and demand will be in equilibrium where those two lines cross. A quantity QF of alcohol will be consumed at a price of PF.

Now consider what happens if a minimum unit price (PMUP) is set, which is above the free market price. The price is now constrained to be PMUP, and consumers will now only be willing to buy a lower quantity, shown as QMUP on the graph. (And if you want YouTube videos from Jodi Beggs again, she explains the concept of minimum pricing here and here).

Consumers are now worse off, by an amount represented by the shaded area on the graph. The light green shaded area A represents how much they are worse off financially. They are paying more than they need to for the alcohol consumed, by an amount PMUP minus PF, for a quantity of alcohol QMUP. To see their overall loss, we must also add the light blue shaded area B. This is the loss of enjoyment as a result of the alcohol they are no longer drinking, which they would have liked to have drunk had it been at the original free market price.

The net result is that consumers are worse off, by the total shaded area A + B. The drinks industry may be better off, as a result of charging higher prices, or worse off if the loss of demand more than makes up for the higher prices, depending on how much sales are affected by the increase in price (the price elasticity of demand, to put it in economics terms).

So a minimum alcohol price would have public health benefits, but at an economic cost to consumers. But we ought also to consider the distributional effects.

The big problem I have with minimum alcohol pricing is not that it represents a cost to consumer per se, but that that cost does not fall equally across society. It is regressive. It disproportionately disadvantages the poor. It may be easy for middle-class health campaigners to forget this, as they sip a nice glass of Châteauneuf-du-Pape which would never be affected by minimum pricing anyway, but some people cannot afford expensive forms of alcoholic drinks. For some people on low incomes, their alcohol consumption may be entirely at the cheaper end of the market, and those people will be disproportionately disadvantaged by minimum alcohol pricing, even if they drink at a level which is not doing them any great harm.

So yeah, maybe the minimum alcohol pricing policy was dropped because of an evil conspiracy by the evil drinks industry (though bear in mind that minimum pricing might actually have increased their profits if the price elasticity of demand was low enough), but just maybe it was dropped for sensible economic reasons.

You comment, correctly, Adam, that the mimimum pricing would only affect the cheap alcohol products. Products which are already more expensive won't become more expensive as their price already exceeds the minimum price.

Assuming that price is related to quality - and I suspect that, particularly at the lowest end of pricing of alcoholic drinks, it largely is, though ideally this would be confirmed by studies - then the cheapest drinks are not going to be high quality. This means that people are unlikely to derive as much pleasure from drinking them. And this suggests that they may be consumed not for pleasure, but out of desperation, to keep withdrawal symptoms at bay; or simply in order to get drunk.

There's another logical step here that may or may not be valid; and this is that the drinking that does most harm to individuals and societies is just this sort of drinking - drinking not for pleasure per se, but with the intention of getting drunk and staving off withdrawal symptoms.

If this is the case, then minimum alcohol pricing will be disproportionately effective in preventing the harms from alcohol, and its health benefits even greater than your simple economic model might suggest.

Of course, there are many steps in this argument, all of which should ideally be confirmed empirically and not just by my speculation; and a failure at any one of them might make my argument invalid! Nevertheless, I suspect the argument may be correct.

Peter.

Hi Peter

Thanks for the comment. Yes, there are a number of steps in your argument, some of which sound pretty safe, others less so.

I'm sure it's true that cheaper drinks are of lower quality and give less pleasure. That, unfortunately, is an inescapable consequence of having a low income. It's true of drinks and a whole load of other things. Of course, that doesn't mean that people derive no pleasure from cheap drinks.

There is some support for your idea that cheap drinks are more likely to be drunk as part of harmful drinking patterns rather than for pleasure. If you look at the Sheffield report, on which the policy was based (or if you're more cynical, which was based on the policy), they claim that the proportion of alcohol consumption that would be affected by a 45 p minimum unit price is 12.5%, 19.5%, and 30.5% for moderate, hazardous, and harmful drinkers respectively.

However, just because harmful drinkers are more likely than moderate drinkers to be affected by a MUP policy, it doesn't automatically follow that those affected by a MUP policy are more likely to be harmful drinkers than moderate drinkers. I couldn't find statistics in the Sheffield report for the relevant stats, but overall, they claim that 77.2% of the population are moderate drinkers, compared with only 5.3% harmful drinkers. So even though harmful drinkers are more likely than moderate drinkers to be affected by the policy, I suspect the majority of those affected by the policy will be moderate drinkers.

So yes, I think you may be right that minimum alcohol pricing will disproportionately reduce consumption among harmful drinkers, which would be a good thing.

However, I'm not sure it's as simple as that. A big problem I have with the Sheffield model (and it's worth noting that there have been quite a few criticisms of the model) is that they assume the same price elasticity of demand for all drinking categories. I'm not sure that's plausible. If you're physically dependent on alcohol, I imagine you have a rather low price elasticity. To be fair, they do report a sensitivity analysis using different price elasticities for different consumption groups, though bizarrely, that analysis assumes higher price elasticity for harmful drinkers. That sounds counterintuitive to me, and I'm not sure why they made that assumption.

Anyway, the policy may or may not have beneficial effects on health that are targeted more at harmful drinkers. But it still causes disadvantageous economic effects disproportionately on those on low incomes, many of whom are moderate drinkers.

Thanks, Adam.

A very interesting discussion!

I have to say that my gut feeling is still in favour of minimum alcohol pricing; but your arguments are making me question my reasons for that. Might there be some sort of paternalistic and classist assumptions about the undeserving poor creeping into my reasoning? I'd be appalled if this were true, but I'll have to scour my conscience to check!

Peter.